Scientists said the ozone hole was recovering. That good news was premature, one study claims

The recovery of the ozone layer — which sits miles above the Earth and protects the planet from ultraviolet radiation — has been celebrated as one of the world’s greatest environmental achievements. But in a new study published Tuesday, some scientists claim it may not be recovering at all, and that the hole may even be expanding.

The findings are in disagreement with widely accepted assessments of the ozone layer’s status, including a recent UN-backed study that showed it would return to 1980s levels as soon as 2040.

In 1987, several countries agreed to ban or phase down the use of more than 100 ozone-depleting chemicals that had caused a “hole” in the layer above Antarctica. The depletion is mainly attributed to the use of chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, which were common in aerosol sprays, solvents and refrigerants.

That ban, agreed under the Montreal Protocol, is widely considered to have been effective in aiding the ozone layer’s recovery.

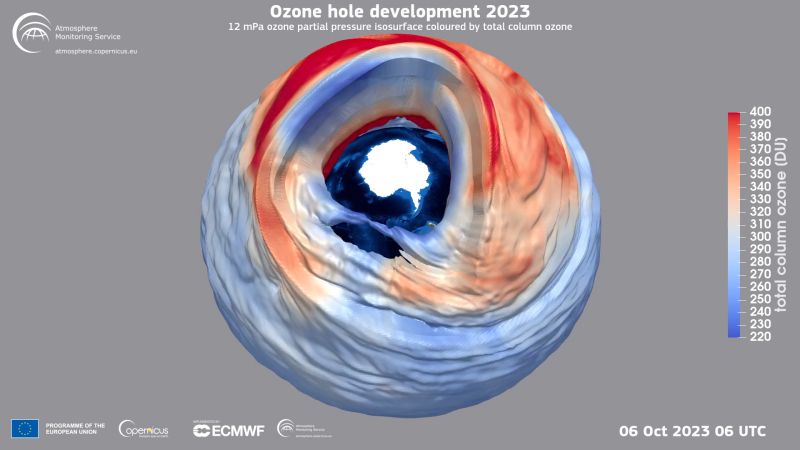

But the hole, which grows over the Antarctic during spring before shrinking again in the summer, reached record sizes in 2020 to 2022, prompting scientists in New Zealand to investigate why.

In a paper, published by Nature Communications, they found that ozone levels have reduced by 26% since 2004 at the core of the hole in the Antarctic springtime.

“This means that the hole has not only remained large in area, but it has also become deeper [i.e. has less ozone] throughout most of Antarctic spring,” said Hannah Kessenich, a PhD Student at the University of Otago and lead author of the study.

“The especially long-lived ozone holes during 2020-2022 fit squarely into this picture, as the size/depth of the hole during October was particularly notable in all three years.”

To reach that conclusion, the scientists analyzed the ozone layer’s behavior from September to November using a satellite instrument. They used historical data to compare that behavior and changing ozone levels, and to measure signs of ozone recovery. They then sought to identify what was driving these changes.

They found that the depletion of ozone and deepening of the hole were a result of changes in the Antarctic polar vortex, a vast swirl of low pressure and very cold air, high above the South Pole.

The study’s authors didn’t go further to explore what was causing those changes, but they acknowledged that many factors could also contribute to ozone depletion, including planet-warming pollution; tiny, airborne particles that are emitted from wildfires and volcanoes; and changes in the solar cycle.

“Altogether, our findings reveal the recent, large ozone holes may not be caused just by CFCs,” Kessenich said. “So, while the Montreal Protocol has been indisputably successful in reducing CFCs over time and preventing environmental catastrophe, the recent persistent Antarctic ozone holes appear to be closely tied to changes in atmospheric dynamics.”

Some scientists are skeptical of the study’s findings, which rely heavily on the holes observed in 2020 to 2022 and use a short period — 19 years — to make conclusions about the long-term health of the ozone layer.

“Existing literature has already found reasons for these large ozone holes: Smoke from the 2019 bushfires and a volcanic eruption (La Soufriere), as well as a general relationship between the polar stratosphere and El Niño Southern Oscillation,” Martin Jucker, a scientist at the Climate Change Research Centre at the University of New South Wales in Australia, told the Science Media Center.

“We know that during La Niña years, the polar vortex in the stratosphere tends to be stronger and colder than usual, which means that ozone concentrations will also be lower during those years. The years 2020-22 have seen a rare triple La Niña, but this relationship is never mentioned in the study.”

He noted the study’s authors said they removed two years in the record — 2002 and 2019 — to ensure that “exceptional events” did not skew their findings.

“Those events have been shown to have strongly decreased the ozone hole size,” he said, “so including those events would probably have nullified any long-term negative trend.”