China’s special envoy is on a Middle East mission. Peace is just part of the picture

Days after the United States’ shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East, which culminated in President Joe Biden’s historic wartime visit to Israel, China has started its own diplomatic hustling in a region teetering on the brink of a wider conflict.

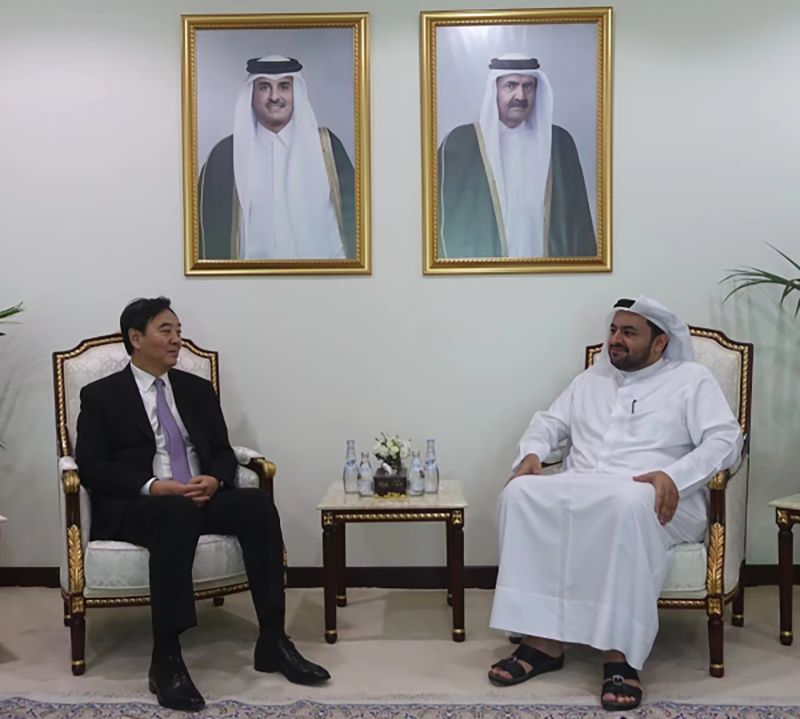

Zhai Jun, Beijing’s special envoy to the Middle East, has embarked on a whirlwind tour of the region aimed at promoting peace talks between Israel and Hamas – even though Beijing still refuses to condemn or even name the Palestinian militant group in any of its statements.

Zhai has traveled to Qatar and attended a peace summit in Egypt, calling for a ceasefire, humanitarian access to Gaza and reiterating China’s support for a two-state solution. It is unclear if he will visit Israel, as Beijing has provided no details of the trip.

But brokering peace is a tall order, especially for a country with little experience or expertise in mediating such a long-running, intractable conflict – in a deeply divided region where it lacks a meaningful political and security presence.

Few experts in or familiar with the Middle East expect Zhai’s trip will lead to any concrete deliverables in peacemaking.

Instead, they view it as a chance for China to tilt the global balance of power further in its favor as the strategic competition with the US heats up.

Beijing is seeking to use the diplomatic mission to shore up its position as a champion of the Arab world and the Global South, which has long been sympathetic to the Palestinian cause and dissatisfied with the American-led world order, experts say.

“China is looking to play a diplomatic role by calling for calm and de-escalation and – at the same time – showing strong support for Palestine,” said Sanam Vakil, director of the Middle East and North Africa program at Chatham House.

“This should be seen sort of opportunistically… China doesn’t have a huge track record of success in trying to be a neutral broker in this conflict. So the most that China can do is offer symbolic diplomatic support.”

Jonathan Fulton, an Abu Dhabi-based senior non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council, said Zhai’s mission will be to “demonstrate China’s solidarity with Arab causes” and to promote “a different vision for the region than the US does.”

“China wants to be seen as an active, responsible great power, but it doesn’t really have the depth of engagement in the region that results in a leading position,” he added.

In pictures: The deadly clashes in Israel and Gaza

‘Weakening Western order’

The spiraling crisis is widening a chasm in the global geopolitical landscape – a divide which has already been sharpened by Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine.

That division was on full display last week. Hours before Biden landed in Israel to show solidarity with America’s closest ally in the Middle East, Chinese leader Xi Jinping hosted his “old friend” Vladimir Putin in Beijing and hailed the deepening political trust between their countries.

The two autocrats held detailed discussions on the conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine, according to Putin, who described them as “common threats” that brought Russia and China closer together.

“Since the war in Ukraine, this alignment has become increasingly obvious. We could call it an axis that is designed to strategically align against the US and US interests globally,” said Vakil, from Chatham House.

“You can include Iran in this relationship too. They have this broad objective of weakening the Western order, and it tactically plays out in the region.”

This tactical alignment is already playing out on the ground. One of the first meetings the Chinese envoy had upon touching down in the Middle East was with his Russian counterpart.

“China and Russia share the same position on the Palestinian issue,” Zhai told Mikhail Bogdanov, Putin’s special envoy for the Middle East and Africa, in Qatar on Thursday.

The position held by Beijing and Moscow cuts a stark contrast to that of Washington, which has thrown its weight behind Israel and dispatched two aircraft carrier strike groups to deter other regional actors from joining the conflict.

China, which had sworn a “zero-tolerance” approach to Islamist militancy by detaining ethnic Uyghurs en masse in its far western region of Xinjiang, has not explicitly condemned Hamas for its terror attacks on Israel – neither has Russia, which had its own history of suppressing political Islam within its own borders.

But both have vocally criticized Israel for its retaliation to the Hamas attacks.

China’s foreign minister accused Israel of going “beyond the scope of self-defense,” while Russia’s UN envoy compared Israel’s relentless shelling of Hamas-controlled Gaza to the brutal siege of Leningrad during World War II.

“There’s a huge difference between the American approach and the Chinese and Russian stance right now,” said Li Mingjiang, an associate professor of international relations at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University.

Russian and Chinese state media have already blamed US policy for the escalating conflict, and as the situation in Gaza deteriorates, Beijing and Moscow will only become even more critical of the US approach, Li said.

Pro-Palestinian stance

China’s pro-Palestinian stance dates back decades and is rooted in revolutionary ideology. In the era of Mao Zedong, the founder of Communist China, Beijing armed and trained Palestinian militant groups as part of its Cold War support for national liberation movements.

After the country’s reform and opening following Mao’s death in 1976, however, China adopted a more pragmatic foreign policy. While it continued to offer political support for the Palestinian cause and became one of the first countries to recognize Palestine as a sovereign state in 1988, Beijing also warmed to Israel and established formal diplomatic relations with the Jewish state in 1992.

Over the past decade, Chinese investment and trade with Israel skyrocketed, especially in the technology sector. In 2017, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu hailed his country and China as a “marriage made in heaven.”

Throughout their economic cooperation, however, China has upheld its political support for the Palestinians, voting in favor of them and against Israel at the United Nations whenever conflicts flared.

Part of that is due to pragmatic interests.

About half of China’s oil imports come from Arab states, which also account for more than 20 votes at the UN – potentially helpful for Beijing when it comes to issues like defending its treatment of Uyghurs.

“China’s view of the Middle East is that Israel is never going to split from the US side, and that means being critical to Israel is going to curry favor with a large bloc of Arab countries,” said the Atlantic Council’s Fulton.

Mediator role

It is not the first time China has expressed an interest in resolving the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Beijing’s aspirations to be a mediator started as early as the 2000s, but remained largely symbolic. China did put forward several vague proposals and invited politically insignificant Palestinian and Israeli figures for talks in Beijing – but those efforts did not lead anywhere.

This time around, experts do not expect the result to be much different, despite China’s recent success in brokering a rapprochement between rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia.

While China’s involvement in the Middle East has grown, its interests there remain primarily economic – and its relations with regional players largely transactional, experts say.

“Beijing possesses little leverage over Hamas and has limited historical involvement in the Arab-Israel conflict. By distancing itself from Israel after the terrorist attack, Beijing has further undermined its influence in Tel Aviv,” said Zhao Tong, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

It also remains to be seen whether China will be willing or able to leverage its close relationship with Iran – which funds and arms both Hamas and Lebanese militant group Hezbollah – to deescalate the war and prevent it from spilling over into a broader conflict.

“I think China certainly is prevailing on Tehran to exercise restraint,” said Vakil with Chatham House. “I personally think the Iranians intend to exercise restraint unless things get out of hand. I don’t think that Iran wants to be involved in a broader regional conflict – so their interests are aligned.”

But while Arab countries may give Zhai a warm reception, few would take Beijing’s peace proposals seriously, Vakil said.

“I don’t think that Middle Eastern states are looking to China to come in and build a diplomatic process (for peacemaking). They are aware of the limitations of what China has on offer,” she said.

“I think there’s very little China can do beyond trying to showcase diplomacy. China doesn’t have the ability to manage the conflict or deescalate this conflict.”