Putin has only himself to blame as infighting engulfs Kremlin insiders

Vladimir Putin, meet the Law of Unintended Consequences.

In the years leading up to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a St. Petersburg-based businessman named Yevgeny Prigozhin emerged as a canny political entrepreneur. Prigozhin and his companies served the interests of the Russian state, advancing Putin’s foreign policy in ways that were both useful and off the books.

Prigozhin’s relatively discreet public profile was his greatest asset. He bankrolled the notorious troll farm that the US government sanctioned for interference in the 2016 US presidential election; created a substantial mercenary force that played a key role in conflicts from Ukraine’s Donbas region to the Syrian civil war; and helped Moscow make a play for influence on the African continent.

All of Prigozhin’s activities gave the Kremlin a fig-leaf of deniability. After all, mercenary activity was technically barred by Russian law, and Putin could always maintain that interference in US elections was merely the work of “patriotic” hackers.

And it also served Putin’s interest to outsource some of the dirty work of sponsoring armed insurrection in eastern Ukraine or holding territory in Syria. Wagner’s existence was not publicly acknowledged, and some of Prigozhin’s operations appeared to be partly self-funded, with various shell companies staking claims to oil and gas facilities and vying for access to gold and other riches.

But all of that changed with the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. By giving Prigozhin free rein to raise a private army, Putin both unleashed the political ambitions of the businessman and surrendered the state’s monopoly on the use of force.

Prigozhin’s feud with the leadership of the Russian military is longstanding, and many observers suggested that this was part of the intricate game of court politics under Putin. The pattern was longstanding: Members of the elite jockeyed for position, influence and business assets, allowing Putin to stay above the fray and dominate the scene as the ultimate arbiter of disputes.

Now Prigozhin has ripped up that contract by taking up the flag of mutiny.

Potentially revolutionary scenario

In an address on national television Saturday, Putin appeared to put Prigozhin on final notice, warning that “those who deliberately chose the path of treachery, who prepared an armed mutiny, who chose the path of blackmail and terrorist methods, will face inevitable punishment, and will answer both to the law and to our people.”

But Putin also nodded to the potentially revolutionary scenario unfolding in the country, something that might portend a calamitous repeat of Russia’s 20th century history.

“This was the same kind of blow that Russia felt in 1917, when the country entered World War I, but had victory stolen from it,” he said. “Intrigues, squabbles, politicking behind the backs of the army and the people turned out to be the greatest shock, the destruction of the army, the collapse of the state, the loss of vast territories, and in the end, the tragedy and civil war.”

Putin, ever one for historical revision, was taking a few liberties with Russian history. “Stolen victory” is not the usual interpretation of Russia’s disastrous involvement in World War I. (And lest we forget, the “stab in the back” narrative around Germany’s defeat in the same war was one of the myths that helped propel the Nazis to power.)

But the question is, which events of 1917 is Putin referring to? The February Revolution began with protests and military mutinies that led to the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the creation of a provisional government. Later that year, an insurrection in Petrograd – today’s St. Petersburg – brought the Bolsheviks to power, precipitating a horrific civil war.

Now Russia appears at risk of another upending calamity, and it’s unclear what role Prigozhin will play: either as a failed mutineer, or with his power and stature enhanced further within Russia.

After Prigozhin’s forces seized Rostov-on-Don, a video surfaced that showed Prigozhin in a tense conversation with two Russian military commanders.

The Wagner chief made clear who was boss, scolding Deputy Minister of Defense Yunus-Bek Yevkurov for addressing him as “ты,” the second person singular used for speaking informally or to an underling.

“Well, who are you (Yevkurov) to talk to me like “you”? Prigozhin said.

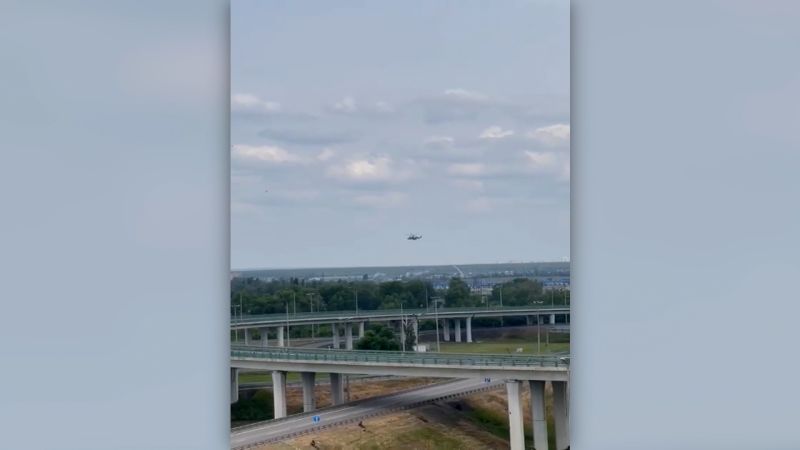

Prigozhin also warns that Wagner’s mutiny will not end in Rostov. “We came here,” he said. “We want to receive the chief of general staff (Gerasimov) and (Defense Minister) Shoigu. “Until they are here we will be located here, blockading the city of Rostov. And we’ll go to Moscow.”